The Trust Crisis Of Banks Worsens Ensuing Initial Collapse Of SVB. A Plus for Crypto

The US banking sector is facing a crisis of trust following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, which has left many Americans, particularly those without insurance for their deposits, anxiously trying to determine if their money is safe. A recent report found that more the 186 banks, or 5% of all banks in the country, are in danger of failing. The article outlines the analysis, identifies the risk factors to watch out for, and explains why investing in cryptocurrency could be a genuine safe-haven option.

As the above screenshot shows, the study is titled ‘Monetary Tightening and US Bank Fragility in 2023; Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?’ It was written by four academics from distinguished universities in the United States on March 13th, 2023.

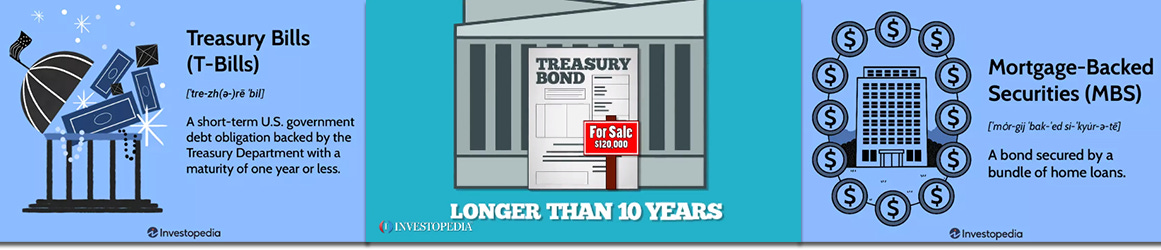

The report begins with a brief explanation of why so many US banks are at risk of going under and pertains to all the assets banks hold on their balance sheets. These are US bonds (US government debt) and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) (bundles of mortgages). US Bonds and MBSs are the safest assets a bank can hold, at least according to regulators, and why banks tend to invest most of their customers' deposits in US bonds and MBSs.

These assets earn interest for the banks and thus make it possible for them to offer services with low or no fees. However, when interest rates rise, the value of US bonds and MBSs decreases. The reasons for this are many, but the main takeaway here is that higher interest rates result in US bonds and MBSs crashing. If the value of these assets falls too much, banks can become temporarily insolvent.

This insolvency is temporary because when US bonds and MBSs mature, meaning the loan terms end, the bank receives the total value of the underlying asset. Again, the mechanics of this are many, but just know that US bonds and MBSs don't lose money if they are held to maturity, and why banks don't report the losses on US bonds and MBSs when interest rates rise.

Most information about losses on debt securities held by banks is immersed in the glossaries in their SEC filings. It is not considered a significant problem until that bank has major liquidity issues. It’s because it's not a loss until they sell, and in the case of US bonds and MBSs, they won't lose anything if they hold them to maturity.

This accounting practice is arguably controversial. These so-called unrealized losses are acceptable if the bank isn't forced to sell any of these assets at a loss, specifically customer withdrawals. It’s what happened to SVB and why it sank. However, there is one crucial detail to keep in mind. 92.5% of SVB's deposits were uninsured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

For context, the FDIC only ensures bank deposits up to $250,000 per account. Any amount above that is considered uninsured. SVB experienced a bank run because its uninsured depositors could see that it had many unrealized losses. This led to speculation that SVB didn't have enough money to honor all withdrawals.

As such, this bank run may not have happened if most deposits were insured, i.e., under $250K per account. SVB had so many uninsured deposits because the bank provided accounts and banking services primarily to small and medium-sized businesses, startups, and entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley. These clients typically require lots of cash liquidity to pay their employees, make acquisitions, etc.

Around $9 trillion of bank deposits in the United States are uninsured, roughly 50% of all bank deposits. Banks have been happily investing these uninsured deposits into US bonds and MBSs. The problem is that interest rates have risen, and their unrealized losses have proliferated. At the end of 2022, US banks collectively had unrealized losses totaling more than $600 billion. Interest rates have risen more since then, so these losses are likely even more prominent now.

In short, US Banks have lots of unrealized losses and also lots of uninsured depositors who are concerned that banks can't honor withdrawals because of these unrealized losses. The authors examined over 4,000 banks in the study to see which ones were most at risk and why.

Unrealized Losses

First, the study highlighted that 42% of all bank deposits had been invested into regular MBSs, with another 24% invested in commercial MBSs, i.e., commercial real estate loans, US bonds, and other asset-backed securities (ABS). The authors then tried to calculate the unrealized losses on these assets. After crunching the numbers, the authors found the following,

“The median value of banks' unrealized losses is around 9% after marking to market. The 5% of banks with worse unrealized losses experience asset decline of around 20%.”

Note that ‘marked to market’ means ‘assuming sold today.’ In lay terms, the average American Bank has unrealized losses of around 10%, and 5% of the most vulnerable banks have unrealized losses of 20%.

So if depositors were to rush and withdraw from these banks, they would get 90% of their money back at the average bank and 80% back at a vulnerable bank. Not surprisingly, these unrealized losses were the smallest for Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIB), including JPMorgan and Bank of America. GSIBs have less than 5% of unrealized losses. The average non-GSIB has 10% unrealized losses, and SVB wasn't even the worst.

The authors found that more than 11% of US banks had larger unrealized losses than SVB when it collapsed. They estimate that as many as 500 other banks could have failed based purely on unrealized losses. The reason why only SVB went down was because of the high number of uninsured deposits. The authors then provide a series of scenarios to showcase how uninsured depositors could react to rising interest rates.

Uninsured Depositors Waking Up

The first scenario assumes that the uninsured depositors stick around and wait. The other three scenarios surmise they withdraw and invest in other assets, which provides a higher interest rate than a savings account. Understand that insolvency fears related to unrealized losses aren't the only reason why uninsured depositors withdraw money from a bank.

The primary reason why they would do this is that they want to earn a high-interest rate on their large deposits. This desire for yield increases as interest rates rise. Unfortunately for the banks, it's hard for them to provide competitive interest rates on savings accounts without losing lots of money. This is why many US banks haven't increased their interest rates on savings accounts, despite interest rates increasing. They’re making lots of money off their depositors. However, if they were to raise interest rates on savings accounts, they wouldn't make nearly as much money.

In the study, the authors assume that most uninsured depositors are sleepy, meaning they aren't rushing to withdraw to earn a higher interest rate elsewhere. However, this is starting to change; besides the banking crisis, the high-interest rates that are still rising in other regions tempt those sleepy uninsured depositors into waking up and moving their money elsewhere. If they do this, banks with large, unrealized losses will start going under as they won't be able to honor all withdrawals.

How Many Banks At Risk?

Naturally, the authors assess whether banks have enough assets to honor these upcoming withdrawals from uninsured depositors. They assume that the FDIC doesn't close down banks that come under stress, which is significant because the FDIC is likely to do this if banks start getting squeezed.

The good news is that all bar two American banks have enough assets to honor withdrawals from uninsured depositors. The bad news is that the authors don't specify which two banks are at risk, but they conclude that this little risk means additional bank runs are unlikely for the time being.

For Good Measure

As an extra, the authors analyzed the possibility of what would happen if uninsured depositors ran. They did a number of simulations of bank runs, from 10% to 100% of uninsured depositors withdrawing their assets.

What's concerning is that the ten banks most at risk of experiencing a bank run are large. As the authors cite in the study,

“The risk of run does not only apply to smaller banks. Out of the 10 largest insolvent banks, 1 has assets above $1 Trillion, 3 have assets above $200 Billion (but less than $1 Trillion), 3 have assets above $100 Billion (but less than $200 Billion), and the remaining 3 have assets greater than $50 Billion (but less than $100 Billion).”

Unfortunately, the authors don't specify which banks these are but reveal how sensitive US banks are to bank runs. They concluded that even if just 10% of uninsured depositors withdrew their money from banks, 66 banks would go under. If 30% of uninsured depositors withdrew their money, 106 banks would go under. If half of all uninsured depositors ran, 186 banks would fail. This underscores that at least a few dozen banks are at risk of going under over the coming months.

This is ultimately due to the fatal combination of significant unrealized losses due to rising interest rates and withdrawals from uninsured depositors seeking higher yields from these rates. The final simulation was if 100% of uninsured deposits withdrew all their assets from US banks. They insisted that this simulation is worth doing to assess the state of the US banking sector. Surprisingly only about half of US banks would go under.

The authors then conclude by highlighting that the value of assets held by US banks is more than $2 trillion lower than what's being reported, thanks to unrealized losses-based accounting. They reiterate that hundreds of banks are at risk of going under if uninsured depositors withdraw. They warned that even small numbers of withdrawals from uninsured depositors could lead to unrealized losses being realized. This would lead to more bank runs, evolving into an even bigger banking crisis than we've seen. They go as far as to suggest regulations to address this.

For starters, banks should start changing how they report their unrealized losses so that bank depositors have a better sense of how underwater their banks are. Because of the lack of transparency, the authors manually calculated these unrealized losses using complex maths. The authors acknowledge that this won't solve the insolvency risks many banks face, so they recommend that banks be forced to increase their capital requirements.

This coincides with what Michael Barr, the Fed’s Vice-chair for Supervision, has been busy doing. Michael had been examining capital requirements for banks before the banking crisis began. Maybe he saw the banking crisis coming or was preparing to take advantage of it to introduce regulations. Michael Bar’s anti-crypto speech indicates the second possibility is the most likely. Michael has been desperate to increase his powers, presumably to consolidate the banking sector to assist in the rollout of a central bank digital currency.

Be Vigilant of The Risk Elements

Which risk factors should you be aware of when analyzing banks? I am not a financial adviser. Still, my research into this convoluted accounting system revealed that the two main risk factors are unrealized losses and uninsured deposits. It is at risk if your bank has many unrealized losses and uninsured deposits. The problem is that it takes work to estimate these unrealized losses. Moreover, not all uninsured deposits are prone to flight. Remember that most of them are required to pay employees at small companies.

Also, as mentioned above, most banks with many uninsured deposits tend to be smaller, i.e., not GSIBs. In theory, this makes them inherently riskier than GSIBs. In practice, though, when a non-GSIB goes under, it gets acquired by a GSIB. This means your assets could be safer at a small bank. If you read the article about bank bail-ins, you'll know that GSIBs can be risky.

If a non-GSIB goes under, it gets acquired by a big bank, and customer deposits are kept, but if a GSIB goes under, customer deposits are used to bail them out. As recently happened with Credit Suisse and its takeover by UBS. The arguably political deal required capital from somewhere to satisfy UBS. According to WSJ, the Swiss government was desperate to avoid the appearance that this was a taxpayer-funded bailout.

GSIBs are also more likely to comply with investment ideologies, like ESG. As discussed in this article, the Bank of America is one of the big institutions behind the ESG movement. Some of its affiliates are introducing individual ESG scores for their customers.

Small banks may also have challenges because around 80% of commercial real estate loans come from small banks. In addition to being wrecked by higher interest rates, commercial real estate is struggling because people must return to the office. 50% of office spaces in the US are empty. This means that small banks are at a higher risk of sitting on larger unrealized losses, which is consistent with the findings of the study.

If that weren't bad enough, these losses would likely increase as time passes, even if interest rates start coming down because work from home is probably here to stay. Even if uninsured depositors are less likely to withdraw from small banks due to the purpose of these deposits, just a small number of withdrawals could therefore cause severe issues for small banks.

The findings of the study suggest this risk is already there. All it takes is 10% of uninsured deposits to move. In sum, small and big banks come with their own risks, and it's up to you to decide which risks you'd instead take. Diversifying your deposits is an option, but the fact that every bank operates using this fractional reserve model means your money will never be genuinely risk-free in their coffers.

Cryptocurrency To The Rescue

This is where cryptocurrency comes in. Cryptocurrencies ostensibly have only one risk: their current price volatility. There are, of course, risks associated with things like improperly written code, but the largest and most established cryptocurrencies have been battle tested every day for over a decade.

Aside from that, cryptocurrencies are one of the best hedges against the banking system. When you hold a cryptocurrency, there is no counterparty risk. That crypto is genuinely yours, and there isn't some greedy banker going and investing your crypto into a basket of risky, commercial real estate loans behind your back.

This characteristic alone makes cryptocurrency valuable. Also, cryptocurrency lets you send a transaction to whoever you want, whenever you want, and for however much you want. This is the true definition of financial freedom, and its importance was fully displayed when Nasdaq halted the trading of bank stocks during the recent banking crisis.

Nobody can turn off the decentralized cryptocurrency exchange and prevent people from trading. You will always be able to trade. Take a second to consider; that blocking transactions, halting trading, and freezing assets will only become more common as CBDCs are rolled out. This will make the financial freedom aspect of cryptocurrency ever more critical, along with the decentralization that underlies it.

Without decentralization, crypto's value proposition quickly disappears. That's why instead of wasting time assessing the unrealized losses and uninsured deposits of banks, you should learn about what makes a cryptocurrency genuinely decentralized. After all, the days of commercial banks are numbered; the thousands of existing banks will inevitably consolidate into a handful of mega banks, and governments will nationalize these mega banks.

Financial freedom in the traditional financial system will be gone when that happens. At the same time, economic freedom in the crypto ecosystem will only continue to grow. By the grace of God, it will rise to the point that it's capable of accommodating the billions of people who will pull out of the traditional financial system as it becomes ever more centralized and ideological.

Both monetary mechanisms will take years to play out, but it's already clear that the global financial system is splitting into two structures: free and sovereign and one that is not. You now have the once-in-a-millennium opportunity to choose which system to participate in. It’s critical to make that decision before it's made for you.

This article is provided for informational purposes only. It is not offered or intended to be used as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.